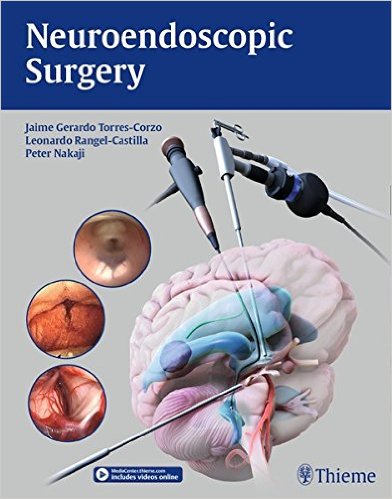

Editors: Jaime Gerardo Torres-Corzo, MD; Leonardo Rangel-Castilla,MD; and Peter Nakaji, MD

Publisher: Thieme – 396 pages, with 326 illustrations

Book Review by: Nano Khilnani

Technological discoveries and the development of various ‘cool’ tools, such as cameras that are smaller and smarter, cold light, endoscopic instruments that are more sophisticated, and fiberoptics are some of the innovations that have greatly helped advance neuroendoscopic surgery in the last 20 years or so. You can view these instruments and tools in this book to understand their functions.

The innovations have also enabled neurosurgeons to develop their knowledge of neuroanatomy. They’ve become experienced and comfortable with neuroendoscopic surgery, and this field has now become a recognized subspecialty within neurosurgery.

Also, minimally invasive procedures and lower morbidity have helped develop greater acceptance of neuroendoscopy both by surgeons and patients.

The purposes of this book when it was being developed, were:

- Describe and illustrate the current indications for intracranial endoscopy

- Compile in a step-by-step fashion the technical details of basic and advanced neuroendoscopic procedures

Who will benefit from the use of this book? Medical students, neurology and neurosurgery residents and fellows, neurosurgeons in including pediatric neurosurgeons, and all physicians who care for and treat patients with intracranial diseases and disorders.

Seventy-one contributors from 10 countries – Australia, Brazil, Germany, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States – wrote the 40 chapters of this book, which are allocated among these six sections listed below.

- Introduction to Neuroendoscopy

- Endoscopic Intraventricular and Basal Cistern Anatomy

- Clinical Indications

- Neuroendoscopic Procedures

- Endoscope-Assisted Microneurosurgical Procedures

- Special Topics in Neuroendoscopy

The authors of the chapters are surgeons and other staff members in various medical centers, as well as professors of neurosurgery in medical schools.

To greatly enhance you learning and practice, find and view 68 surgical videos and animations on procedures covered in this volume by going online to: www.MediaCenter.Thieme.com. During the registration process, enter the access code found on the back page of this book.

One of the important and interesting chapters in this book is chapter 3, Development of a Flexible Neuroendoscope, written by Kazunori Oka. This short chapter of six pages consists of the following topics of discussion:

- Introduction

- Development of a Flexible, Steerable Neuroendoscope

- Initial Designs

- Present Improvements

- Future Plans

- Conclusion

- References

Endoscopic surgery began to be performed in the early 1900s. But the lack of suitable instruments led to poor operative results, thus impeding worldwide acceptance and popularity. Since the 1970s however, endoscopes have been more widely used.

The author writes: “neurosurgeons tend to prefer open surgery, with direct visualization of the lesion, and the ability to expand the approach to allow easy observation of its surroundings. Skillful neurosurgeons with proficient techniques can often minimize the size of the operative trajectory” However, there are pitfalls in open neurosurgery.

Neuroendoscopic techniques have had to be adapted to conditions such as ventricles being filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and the fact that brain tissue, while solid, is soft and fragile. So over the years, neuroendoscopes have been modified to improve accuracy and safety. Also, neurosurgeons discovered that surgery can be performed better and with minimal neurovascular damage with an endoscope than with microscopic surgery

Sensing the need for safe, minimally invasive neurosurgery for treatment of many neurological pathologies, a flexible, steerable, fiberoptic neuroendoscope was developed in 1986 in a collaborative effort between Kazunori Oka, the author of this chapter, and the Tokyo-based Olympus Optical Company.

They determined that the ideal width of the outer diameter was 4 mm, equipped with an inner channel with a 2 mm inner diameter. They initially worked with two design concepts, one for observation, and the second for surgery. These were waterproof and lighter than the endoscopes used in other fields such as gastroenterology, gynecology, pulmonary medicine, and urology.

In this chapter, several images are presented, including one of a television monitor that shows large views of the areas of the brain which are being operated upon. The images show high luminosity, deep focus, and clear views of the areas where surgery is being performed.

Editors:

Jaime Gerardo Torres-Corzo, MD is Professor and Chairman of Neurosurgery, and Director of Neuroendoscopic Surgery at the School of Medicine at Universidad Autonoma de San Luis Potosi in San Luis Potosi, Mexico.

Leonardo Rangel-Castilla,MD is Clinical Assistant Professor of Neuroendovascular Surgery at University of Buffalo Neurosurgery in Buffalo, New York; and Assistant Professor of Cerebrovascular and Skull Base Surgery at Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Arizona.

Peter Nakaji, MD is Professor of Neurosurgery, AND Neurosurgery Residency Program Director at Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Arizona.